There’s a hole in the middle of our AIDS programme

This hole is called medicine stock-outs. It is caused mainly by poor management, and no matter how good our national programme and health minister are, unless the implementers – the provinces – can improve health service delivery, we will not only fail to overcome HIV but we stand to develop a monster called drug-resistant HIV.

This hole is called medicine stock-outs. It is caused mainly by poor management, and no matter how good our national programme and health minister are, unless the implementers – the provinces – can improve health service delivery, we will not only fail to overcome HIV but we stand to develop a monster called drug-resistant HIV.

Between 2009 and 2011, there was a 75 percent increase in South Africans getting access to antiretroviral (ARV) treatment – and we now have the world’s biggest treatment programme with some 2,4 million people started on the lifelong, life-saving medicine.

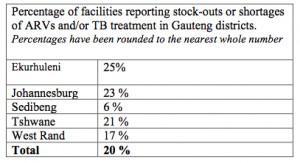

But medicine shortages over the past year have jeopardised the programme. One in five health facilities polled recently reported ARV shortages in the past few months, potentially affecting 420 000 patients. This is according to a report released yesterday by Stop the Stock-outs Campaign, based on a recent telephone survey of 2 139 health facilities.

HIV is a virus that mutates or changes as it grows, so it can easily develop resistance to a single medicine. Thus, people on HIV treatment get three different medicines – triple therapy – that target different parts of the virus’ life cycle.

Treatment interruptions give the virus an opportunity to adapt to the medicines and develop resistance, which means that the medicine will no longer stop the growth of the virus, which will spell weakened immunity and even death for those with HIV.

Ahead of World AIDS Day on Sunday, AIDS doctors and activists all listed the medicine stock-outs as the biggest challenge facing the HIV fight.

“There has been a lot of progress against HIV but this is being undermined by provincial dysfunction,” said Marcus Low, the Treatment Action Campaign’s head of policy, who described the widespread ARV shortages as “shocking”.

“The extent of medicine shortages, especially of ARVs, in South Africa is enormous, far beyond previous estimations, and affects most provinces,” according to the Stop the Stockouts report.

“Medical consequences and costs to the health system and patients can be grave, including drug resistance, decreasing immunity, increased risk of opportunistic infections and transmission of HIV and tuberculosis (TB), ultimately leading to more illness and death.”

Dr Francesca Conradie, president of the Southern African HIV Clinicians’ Society, listed ARV stock-outs as the biggest problem, followed by “a healthcare system that is not able to deal with the volume of patients”, and tuberculosis, which preys of people with weak immune systems.

“South Africa has a population of hyper-susceptible individuals [to TB infection] and a poorly functioning TB programme,” said Conradie. “We have one of the highest incidence rates (new cases) of TB in the world – about one percent per annum and an increasing number of multi-drug resistant and extensively drug-resistant cases.”

Drug-resistant tuberculosis is a human-created problem caused by people not taking their medication properly. We cannot afford the same thing to happen to HIV, leaving few medical options for the country’s 5.6 million HIV positive people.

Although some 200 000 South Africans are predicted to die this year of AIDS-related infections, according to Statistics South Africa, the country has made massive advances in its fight against HIV.

One of the most striking achievements is the reduction of mothers passing HIV to their babies to around 2,5%. HIV was one of the biggest causes of deaths in children under the age of five, so this mortality rate is slowly going down as a result.

The extensive ARV rollout is keeping more people alive and our life expectancy, which was lower than the war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo a few years ago, has inched up to 58 years.

In the provinces most affected by HIV, the improvement in life expectancy is striking. For example, in rural Umkhanyakude District in KwaZulu-Natal, life expectancy jumped by 11 years between 2003 and 2011. In 2003, the average person died at 49 but by 2011, they lived to 60.

This is according to research conducted by the Africa Centre, which was published earlier this year in Science, a leading international scientific journal.

“The public sector scale-up of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has transformed health in this community,” said the study’s lead author Jacob Bor of the Africa Centre and Harvard School of Public Health. “Before ART became widely available, most people were dying in their 30s and 40s. Now people are living to pension age and beyond.”

Africa Centre Director Professor Marie-Louise Newell added that the rapid scale-up of ART in Umkhanyakude had achieved “massive results”.

“The reduction in mortality has been very visible to the members of the community. Whereas six years ago there was at least one funeral every weekend, now this is more like one a month,” said Newell.

Earlier this year, the health department made ARVs even easier to take by introducing the “fixed-dose combination” pill – a single pill that combined all three pills previously taken into one. While very handy for patients, it means that if there are stockouts, patients won’t get a single one of the three ARVs they need.

Aside from supply issues, keeping millions of people on ARV treatment for their entire lives, and managing the inevitable drug resistance that will result, requires a robust health system.

Gauteng province has doubled the number of people on ARVs in the past year alone, and now has over half-a-million people on treatment. Yet one-fifth of the province’s health facilities polled reported ARV stock-outs in the past three months.

Gauteng province has doubled the number of people on ARVs in the past year alone, and now has over half-a-million people on treatment. Yet one-fifth of the province’s health facilities polled reported ARV stock-outs in the past three months.

Nationally, we don’t actually know how many of the patients who started taking ARVs are still on them and if not, why they have stopped.

“Retention of people in care is a big issue,” said the TAC’s Low. “We are told that there are 2.4million people on ARVs and that is incredible if it is true. But we don’t know how many people are still on treatment because monitoring patients in the health system is weak, and needs to be fixed.”

Low added that the rollout of much-lauded National Health Insurance (NHI) scheme, supposed to improve health service delivery, was moving way too slowly in the pilot districts and that most people were not aware of what was happening.

It is an open secret that Treasury has failed to allocate enough money to the NHI pilots, and there are already difficulties in recruiting enough skilled health workers to all the posts.

Compounding the lack of resources and a shortage of health workers, is the lack of political will of provinces such as the Eastern Cape to clean out their own corruption so that they can deliver acceptable services.

The international slogan of “towards zero HIV infections” this AIDS Day will amount to zero unless our serious health systems challenges, including the epidemic of corruption, are addressed. – Health-e News Service.

Read more Health-e coverage of stock outs in South Africa

Author

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Unless otherwise noted, you can republish our articles for free under a Creative Commons license. Here’s what you need to know:

You have to credit Health-e News. In the byline, we prefer “Author Name, Publication.” At the top of the text of your story, include a line that reads: “This story was originally published by Health-e News.” You must link the word “Health-e News” to the original URL of the story.

You must include all of the links from our story, including our newsletter sign up link.

If you use canonical metadata, please use the Health-e News URL. For more information about canonical metadata, click here.

You can’t edit our material, except to reflect relative changes in time, location and editorial style. (For example, “yesterday” can be changed to “last week”)

You have no rights to sell, license, syndicate, or otherwise represent yourself as the authorized owner of our material to any third parties. This means that you cannot actively publish or submit our work for syndication to third party platforms or apps like Apple News or Google News. Health-e News understands that publishers cannot fully control when certain third parties automatically summarise or crawl content from publishers’ own sites.

You can’t republish our material wholesale, or automatically; you need to select stories to be republished individually.

If you share republished stories on social media, we’d appreciate being tagged in your posts. You can find us on Twitter @HealthENews, Instagram @healthenews, and Facebook Health-e News Service.

You can grab HTML code for our stories easily. Click on the Creative Commons logo on our stories. You’ll find it with the other share buttons.

If you have any other questions, contact info@health-e.org.za.

There’s a hole in the middle of our AIDS programme

by kerrycullinan, Health-e News

November 29, 2013